|

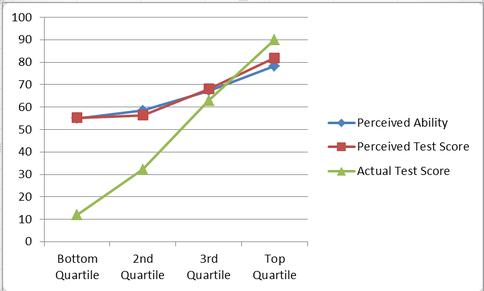

Contributed by Elias Saltz In my earlier post here on Let’s Fix Construction, I listed a number of ways in which architects contribute to problems that lead us to the project of looking for ways we can fix construction. Among that list, I posited “Architects, and humans in general, to be fair, have a overly optimistic view of their own knowledge and competence. This is known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. As a result, they forcefully promote making decisions based on faulty information that they have high levels of confidence in.” I thought it might be fun to look at this a little deeper because having (and living by) an honest assessment of our own competence is really challenging. Dunning-Kruger Effect The Dunning-Kruger Effect is named after a paper published in 1999 by psychologist David Dunning and his graduate student, Justin Kruger. The effect has been substantiated in subsequent studies and is generally accepted to be a “hard-wired” part of human psychology. In their original study, they asked subjects to take tests in a variety of subjects and before learning the results were asked to estimate their abilities in the subject area and their performance on the tests. They found that other than the top few percent of test-takers, subjects grossly overestimated their competence. The chart above illustrates the results. The striking part: everyone believes they’re above average. Of course, the very definition of “average” makes that impossible.

In a later article, Dunning makes some additional observations about the Dunning-Kruger Effect, including this: “An ignorant mind is precisely not a spotless, empty vessel, but one that’s filled with the clutter of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories, facts, intuitions, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that regrettably have the look and feel of useful and accurate knowledge.” The longer we live and the more things we experience, the more what-we-take-to-be-knowledge we have in our heads. We take a lifetime’s worth of useless clutter in our heads and it makes us feel like we know more than we do. While the Dunning-Kruger Effect may be built into our brains, that doesn’t mean we need to be driven by it. The main way to combat its effects are through careful self-reflection and metacognition. A good place to start is the moment when you realize you’re judging someone else for their apparent idiocy. Consider how it would feel to be judged in the same way the next time you are wrong about something. Rather than being tempted to believe that any particular idiocy doesn’t apply to you, ask yourself what you think you know about that topic, how confident you are in that knowledge, and, most importantly, how you think you know it. Your mental litany should go, “what do I think I know and how do I think I know it?” Instead of feeling defensive about being wrong and making up excuses for maintaining an erroneous belief, (which is our default stance - this is part of another powerful metal effect called cognitive dissonance), train yourself to get pleasure when you update your beliefs when presented with compelling evidence that you were wrong. The reason I think it’s useful to discuss Dunning-Kruger in this series of posts is that I think architecture is probably more rife with it than other learned professions. That begins in our education, in which for most schools training architecture students how much they don’t know simply isn’t part of the curriculum. Instead, in architecture school, ideas (“concepts”) stand in for knowledge and learning how to draw is given heavier weight than learning the profession. Architecture students are taught a lot about design but next to nothing about building technology, specifications, or practice. [Aside -- Speaking of weight, back when I was in school we used Sweets™ Catalogs as ballast for models, but it was also enlightening to page through them just to see the myriad building products that exist in the world of which I had so little knowledge. Also, Sweets ™ was the first place I encountered MasterFormat divisions. Now, I don’t think the paper version of Sweets™ even exists.] Contrast architectural with medical school: there the knowledge gap between the students and practitioners is constantly being emphasized and made clear through verbal and written assessments. Medical students are reminded over and over that they have massive amounts to learn, and taught to be humble. Maybe it’s a status thing; architects tend to believe architecture is a high status profession. Most architects believe that having more completed projects in the world gives them higher status and more knowledge and the right to claim to be wise and espouse ‘deep thoughts’. However, we’d be more wise to understand and remember that Dunning-Kruger shows that what feels like knowledge often isn’t anything more than mind clutter. Skeptical blogger and podcaster Steve Novella wrote this when offering advice on how to combat Dunning-Kruger in yourself: Think about some area in which you have a great deal of knowledge in the expert to mastery level (or maybe just a special interest with above average knowledge). Now, think about how much the average person knows about your area of specialty. Not only do they know comparatively very little, they likely have no idea how little they know, and how much specialized knowledge even exists. Here comes the critical part – now realize that you are as ignorant as the average person is every other area of knowledge in which you are not expert. Assume you know less than you think you know. Assume that stuff you believe now is wrong (and be ready to change your mind).

1 Comment

Evan Adams

10/11/2016 01:15:04 pm

"think about how much the average person knows about your area of specialty. Not only do they know comparatively very little, they likely have no idea how little they know, and how much specialized knowledge even exists. Here comes the critical part – now realize that you are as ignorant as the average person is every other area of knowledge in which you are not expert."

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AboutLet's Fix Construction is an avenue to offer creative solutions, separate myths from facts and erase misconceptions about the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry. Check out Cherise's latest podcast

Get blog post notifications hereArchives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed