|

Contributed by Eric D. Lussier I feel extremely fortunate to live just next door to Burlington, Vermont, in a fantastic little town called Colchester. How next door? I live just six miles from Burlington's City Hall.

For those that have visited Burlington, you know just how special of a city it is. And for all of those that I've talked to that have never visited Burlington, they've heard what you've probably heard. It's beautiful, it's the home of Bernie and Ben and Jerry's and Phish, it's also very left-leaning and it's on the list to visit some day. Little ol' Burlington, population 42,239 as of 2017, happens to be the first city in the nation to source all energy from renewable sources in 2014. And just two weeks ago, our Mayor, Miro Weinberger, announced a plan to make Burlington a net zero energy city by 2030. In doing so, he said “I know that many Burlingtonians believe, as I do, that we are in a climate emergency, and at the same time, that it can feel tough to know how to respond to the scale of this problem. With this roadmap in hand, we now have clear next steps for what we can do to respond at the local level to this global crisis." This roadmap includes four main pathways which include:

Burlington may be ahead of the curve when it comes to this difficult conversation and gameplan that is quickly becoming a global crisis. Climate emergency is a perfect term for what we are experiencing, not only at a local level, but also at a global level. This global crisis is under more of a magnifying glass this week as we celebrate World Green Building Week, which is an annual campaign that motivates and empowers us all to deliver greener buildings. The campaign in 2019 aims to raise greater awareness of the carbon emissions from all stages of a building’s lifecycle, and encourage new practices and new ways of thinking to work towards reducing carbon emissions from buildings. Did you know buildings and construction are responsible for 39% of global energy-related carbon emissions? 28% of these emissions come from the operational "in-use" phase – to heat, power and cool them, while 11% of these emissions are attributed to embodied carbon emissions, which refers to carbon that is released during the construction process and material manufacturing. As part of this 10th annual World Green Building Week, the World Green Building Council has issued a bold new vision for how buildings and infrastructure around the world can reach 40% less embodied carbon emissions by 2030, and achieve 100% net zero emissions buildings by 2050. Burlington may be a few years ahead of the curve, but still needs to hit that goal of 2030. As for you and your firm, what are you doing to ensure we’re building a better future?

0 Comments

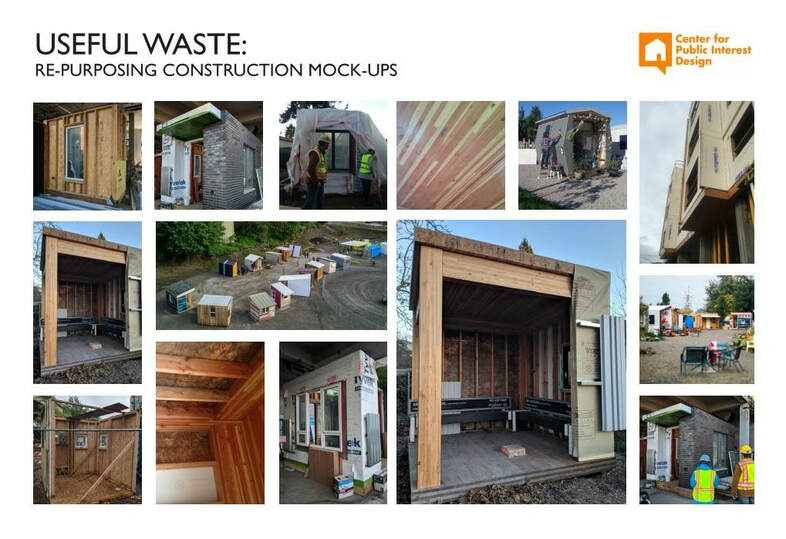

Contributed by Julia Mollner Imagine a construction site where material waste is minimized or absent; where any excess usable material is intentionally set aside; where project teams collectively choose to reuse.

The Useful Waste Initiative was conceived with this idea in mind; the idea that preemptive intentional action can divert excess construction waste and better serve the community. As a program of Portland State University’s Center for Public Interest Design, this initiative aligns with its mission to aid underserved communities while working within the typical construction workflow. The intent of this initiative is to redefine what is considered waste, and to utilize an overlooked material resource - construction mock-ups - by re-purposing them while responding to pressing social needs. Mock-ups play an integral role on the construction site by demonstrating and establishing high quality procedures for building systems, sequencing, and installation. Project teams use the structure to perform tests, understand material compatibility, and demonstrate design aesthetics. It is used for quality assurance and a demonstration of design. Yet, as mock-ups act to save time and money with building installation errors, these mock-ups are seen as temporary structures and typically end up at landfills, which create the opposite output: waste and emissions. Backtrack two years ago, when the Kenton’s Women Village in Portland, Oregon was going through the development process. This village is based on other local villages such as Right 2 Dream Too, Dignity Village, and Hazelnut Grove, which have their own communal governance. The village-model provides what living on the streets often cannot - privacy, personal safety, property safety, a quiet space, access to clean drinking and bathing water, and cooking facilities. Villages are comprised of small sleeping rooms, also called “sleeping pods”, which are built by individuals or village residents to house one or two people. These sleeping pods create a communal village of residents under a self-governance. With Portland in a State of Housing Emergency, these villages started a local mindset shift. Although these “sleeping pods” do not have electricity or plumbing, they serve a critical purpose - housing first. After my participation in the Kenton Women’s Village construction and alongside my own professional construction contract administration experience, I began questioning what purpose a mock-up could serve after use on a construction site. Do these structures - similar to tiny homes - need to go to the landfill? Contributed by Brian Stroik CRASH!

BANG! WOW! That was cool - the Crash Test Dummies have done their job again! The automotive industry found a way to ensure the safety performance for their deliverable for all manufacturers to owners (us), through testing and validation. Yet when we approach the subject of performance mockups within the building community, people seemed shocked at the suggestion. After all, it might cost something to make sure it gets done right the first time – heaven forbid! Now, consider this: buildings today utilize thousands of products, from hundreds of manufacturers, with thousands of different chemical compositions, being installed by a group with a known labor shortage, managed by groups with all different delivery methods. Try and figure out that matrix of possible outcomes. Add in the fact that very few architectural schools teach building physics to students for the understanding of heat, air, and moisture transfer, and it is no wonder insurance claims and litigation from moisture and water issues in construction is a billion-dollar industry annually. Let’s also ask the question: how many architectural firms have chemists or research and development labs or full-scale testing facilities? Very few. But as an industry, we are asking the architect to provide product choices in specifications and properly designed and detailed projects, with the full knowledge that no single person or firm could possibly know or understand all the technologies available for all six sides of the enclosure. So…how can the Owner be assured his building is being properly built? Use the building industry’s “Crash Test Dummy” – the performance mockup. The performance mockup is used to validate the design, product selection, and proper installation of materials, prior to the final installation on the building. Would you build a car in your backyard for your 16-year-old to drive on the expressway at 70 MPH? If you answered no, then why would you expect a unique combination of design, materials, and installers to be able to successfully provide an Owner with a leak-free building on their first try? Remember…. every building is UNIQUE. Even if you use the exact same design from project to project, you must add in the experience, or lack thereof, of the installers for each building. So, consider even if you design and select the exact same materials for two identical buildings, there is no feasible way they could be built in the exact same weather conditions, with the exact same labor force. It is impossible! The performance mockup can be built and tested in a myriad of configurations and at all levels of cost. The most important part is that they are tested - for water leakage, air leakage, thermal concerns and durability. Make sure people installing the mockup are also going to be working on the project. What good does it do the project if the knowledge gained by the mockup is not available for the actual construction of the project? Let’s do it right on the building the first time and aim to get the lawyers and litigation out of construction. This is the first in a four-part series on performance mockups. Stay tuned for more information. • Types of Mockups • Testing of Performance Mockups • Transferring knowledge from the Performance Mockup Contributed by Eric D. Lussier While hosting a Let’s Fix Construction workshop at the AIA Conference in New York City this past Friday, a theme struck me during a discussion after a team was presenting their real-world solutions to the question that was posed to them. By nature, this theme seems opposite of the AEC industry in general.

One of the many reasons why Cherise Lakeside and myself have been travelling and presenting over the last year is to help eliminate the phrase “we’ve always done it this way” in construction. The industry remains stuck in many ways and tends to not implement changes easily, nor quickly. So, I find it nothing short of ironic that the theme that struck, the term “FAST” seems so prevalent, including one long term usage, one definition that is on the cusp and one that I’m declaring. Fast-Track Construction While not an official project delivery method on its own, the term fast-track construction seems so common in the industry nowadays, that one almost assumes the term refers to the overall pace of the construction schedule. However, according to the CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide, ‘Fast-track (construction) is the process of overlapping activities to permit portions of construction to start prior to completion of the overall design. The project schedule may require that portions of the design and construction occur concurrently.’ It’s my belief that the presumed definition and the true definition of fast-track construction are now blurred. Overall project construction schedules and durations have been shortened for years now, even while lead times are longer than ever for certain material procurement and the workforce isn’t supporting these timelines. Fast-Track Design Before a shovel can be put in the ground and create the new blurred definition of fast-track construction, demands are being put on designers more and more in 2018 by Owners to create what I’m going to call “Fast-track design”. The first six (of eight) stages of the life cycle of a facility traditionally moves from project conception to project delivery to design (schematic design and design development) to construction documents to procurement to construction. While these phases could take anywhere from a few years to upwards of twenty years in the past, a new norm has compressed this timeline upwards of eighty percent in some cases. While discussing public school design with a specifier recently, they recollected how a new high school design used to be allotted eighteen to twenty-four months for design in the past and what has become all too common is the same design is now being drawn and bid in as little as six to nine months. Contributed by Eric Weisbrot Construction as an industry has noticeably lagged in moving operations toward a more digital realm compared to other business verticals. A report published by McKinsey in 2017 highlighted this truth, citing a near stagnant rate of productivity growth among construction businesses. Comparing that to the 1,500 percent growth of industries like manufacturing and agriculture, it is clear construction is ripe for disruption. But those who have earned a living from the construction business, including licensed and bonded contractors and project managers, have been slow to adopt new technology over the years.

Now, however, the industry is in dire need of change. Many statistics show a labor shortage in construction, high occurrences of waste and inefficiencies on job sites, as well as skyrocketing budgets and capital spending for substantial projects. In order to combat these growing concerns and bring technology into the fold, the construction environment is starting to grasp the power of the following revolutionary changes fueled by technological tools and resources. Here are seven ways technology is influencing construction today. Autonomous Machinery Countless technology firms are focusing their energy on developing autonomous construction machinery, some led by former tech company engineers and designers. Self-operating machines, including bulldozers, excavators, and cranes, are already operating on sites around the world. Their mainstream entrance into the market is imminent in the next several years. Machines that do not require a human touch can be used to tackle repetitive, simple tasks that take skilled workers significant time and effort to complete. The inclusion of robotics in construction has the potential to reduce waste and inefficiencies across the board. Drones and 3D Printing In addition to self-operating machinery, the technology behind drones and 3D printing is also making its debut in the construction field. Drones have been used to help monitor job site progress, as well as lend a hand in the inspection process for projects both small and large. 3D printing offers a new way of designing projects and creating some structures that would otherwise require ample time and effort by individual construction professionals. These technologies have other far-reaching implications in construction as they become more developed and more widely used. |

AboutLet's Fix Construction is an avenue to offer creative solutions, separate myths from facts and erase misconceptions about the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry. Check out Cherise's latest podcast

Get blog post notifications hereArchives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed