|

Contributed by Randy Nishimura Is the architectural profession in need of revitalization or reinvention? In a provocative blog post (Please. Stop the Reinvention Talk), fellow blogger and specifications writer Liz O’Sullivan issued a rejoinder to management consultant James P. Cramer, and his article for DesignIntelligence entitled Competing for the Future. Having considered both perspectives, it’s my turn to comment. Jim Cramer takes issue with architects who suffer from a lack of nerve and have given in to a cynical and dark pessimism about the future of professional practice. He questions why some architects dwell as much as they do upon inwardly focused priorities rather than exploring new models and entrepreneurial visions for the design professions and tomorrow’s A/E/C industry. It’s his belief that “the game has changed” and that innovation and change management need to be an integral part of the curricula in schools of architecture. He is an advocate for reinventing the profession. Liz bristles at the notion that reinvention is necessary. Instead, she believes we must do a better job of meeting the needs that owners have now, that we used to meet, and no longer do. She points out that owners haven’t changed but architects have. We’ve unwittingly surrendered much of the design and construction landscape to others and in the process diminished our influence and relevance. Liz asserts owners will stop looking elsewhere for the services we used to provide if we simply reclaim our territory and prove our value once more. She believes in revitalization rather than reinvention. This needn’t be an “either/or” dilemma. We should embrace all possibilities. We must address the complexities and yes, the contradictions, of current professional practice. We can revitalize and reinvent ourselves at the same time. As I stated in my response to Liz’s earlier Take Back the Reins post and as Liz herself acknowledges, a crucial challenge confronting architecture is the exponential growth in its complexity and scope. This development prompts specialization and the balkanization of our profession because it is increasingly difficult for architects to acquire detailed expertise in all areas of focus. The problem is essentially a budgeting exercise: how do we allocate limited resources (time and money) in the development of future architects? I argued we would be losers if we played a zero-sum game in which sacrificing design acumen is necessary to acquire essential technical know-how. Exercising my privilege as the author of that statement, I’ll now amend it by substituting “critical thinking” for “design acumen.” We cannot afford to shortchange the teaching of critical thinking, analysis, and integrative problem solving in our schools of architecture. These are the core competencies that form the indispensible foundation of a skill set unique to architects. A classic schooling in architecture ingrains the ability to think broadly and critically. We need to view the world from the widest perspective possible, and apply critical thinking to every aspect of professional practice. To do otherwise is to abandon our duty as stewards of the built environment. This duty is profound: Architecture is not an autonomous pursuit. Regardless of how much responsibility we have ceded to other entities, we have impactful roles to play when it comes to a wide spectrum of challenges faced by our society. We still exert influence today upon the creation of effective and grounded design solutions. We can expand this influence and revitalize our profession by once again assuming a broad leadership role on every design and construction project. Click Read More ------> Critical thinking—a willingness to consider and integrate alternative perspectives, imagine new possibilities, and foster criticality in others—is not the product of an overly focused, parochial education. And yet, that’s where some schools of architecture appear to be headed. Short-term exigency and bottom-line economics have contributed to an obsessive pursuit of lucrative research funding and a focus upon market-driven differentiation at colleges and universities across the country.

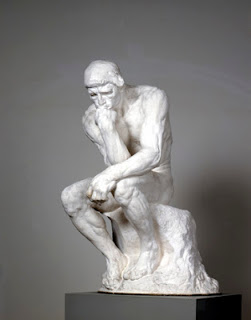

A case in point is my alma mater, the University of Oregon. The UO School of Architecture & Allied Arts is widely recognized as a preeminent institution when it comes to sustainable design. However, the school has so wholly embraced this reputation that it may become the proverbial tail wagging the dog. Sustainability is a crucial issue that should be at the forefront of our thinking; however, it should not crowd out other considerations fundamental to the education of future architects. An unintended consequence of Oregon’s emphasis upon sustainability and move away from design theory may ultimately be a generation of graduates who lack the ability to question assumptions and think critically. This would be unfortunate. The same holds true if we believe enhancing the stature of our profession is simply a matter of restoring a respected measure of technical competence and responsibility. Don’t get me wrong: I definitely agree with Liz when it comes to the need to supplement the practical education of emerging professionals. I am a strong advocate for what the Construction Specifications Institute can do in this regard. Our profession should do more to popularize CSI’s certification programs. Doing so would raise the general fluency of young architects with construction terminology, practices, and documentation standards. My point is that architects are not merely technicians. We need to be as well-rounded as possible to be truly effective, the most so of all the players in the entire design and construction arena. Restoration of our traditional role in the building design and construction processes is one side of the coin. It is revitalization. The other side is reinvention, but I regard reinvention in conceptually broader terms than Jim Cramer does. Imagination and entrepreneurial spirit are fantastic but they do not define who we are. Fundamentally, architects are synthesizers, problem-solvers, orchestra conductors, and thinkers of the highest order. We can both reinvent ourselves and revitalize our profession by demonstrating to everyone the value of architects. We can do this by rising up to see the big picture. We can assume the mantle as critical thinkers about the built environment. Reinvention? Revitalization? Or both? Read what Liz and Jim each say and come to your own conclusion.

4 Comments

Ujjval Vyas

8/22/2016 01:30:58 am

Randy,

Reply

8/22/2016 11:12:58 am

Ujjval: Without a doubt, your critiques of my blog posts are incredibly challenging and cause for reflection. In this instance, my rebuttal (as lacking in rigor as it may be) is founded upon my belief that architects can too easily sort themselves into confining silos of expertise and that doing so is detrimental to the profession as a whole.

Reply

8/24/2016 05:53:00 pm

Randy, in the last paragraph you said, "Nor would any architect suggest that fulfilling one's duty to the client and the public at large is anything less than paramount" 8/30/2016 04:03:09 pm

I have been teaching graduate students in Architecture a one hour Contract Administration and a one hour Construction Specifications Class for fifteen years. They are both elective classes and the only class that they are required to take that even comes close to understanding the business of architecture is the practices class. I disagree that the education of young architects needs to be "supplemented". It needs to be a part of the curriculum. I am a big fan of Liz, however there are a couple of things I would like to say about her post.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AboutLet's Fix Construction is an avenue to offer creative solutions, separate myths from facts and erase misconceptions about the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry. Check out Cherise's latest podcast

Get blog post notifications hereArchives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed