|

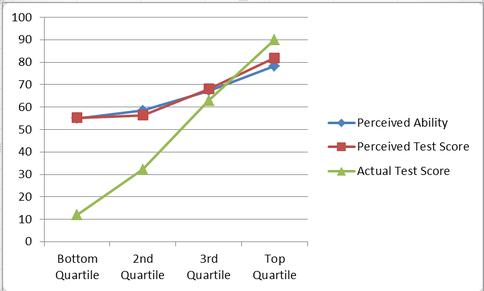

Contributed by Elias Saltz In my earlier post here on Let’s Fix Construction, I listed a number of ways in which architects contribute to problems that lead us to the project of looking for ways we can fix construction. Among that list, I posited “Architects, and humans in general, to be fair, have a overly optimistic view of their own knowledge and competence. This is known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. As a result, they forcefully promote making decisions based on faulty information that they have high levels of confidence in.” I thought it might be fun to look at this a little deeper because having (and living by) an honest assessment of our own competence is really challenging. Dunning-Kruger Effect The Dunning-Kruger Effect is named after a paper published in 1999 by psychologist David Dunning and his graduate student, Justin Kruger. The effect has been substantiated in subsequent studies and is generally accepted to be a “hard-wired” part of human psychology. In their original study, they asked subjects to take tests in a variety of subjects and before learning the results were asked to estimate their abilities in the subject area and their performance on the tests. They found that other than the top few percent of test-takers, subjects grossly overestimated their competence. The chart above illustrates the results. The striking part: everyone believes they’re above average. Of course, the very definition of “average” makes that impossible.

In a later article, Dunning makes some additional observations about the Dunning-Kruger Effect, including this: “An ignorant mind is precisely not a spotless, empty vessel, but one that’s filled with the clutter of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories, facts, intuitions, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that regrettably have the look and feel of useful and accurate knowledge.” The longer we live and the more things we experience, the more what-we-take-to-be-knowledge we have in our heads. We take a lifetime’s worth of useless clutter in our heads and it makes us feel like we know more than we do. While the Dunning-Kruger Effect may be built into our brains, that doesn’t mean we need to be driven by it. The main way to combat its effects are through careful self-reflection and metacognition. A good place to start is the moment when you realize you’re judging someone else for their apparent idiocy. Consider how it would feel to be judged in the same way the next time you are wrong about something. Rather than being tempted to believe that any particular idiocy doesn’t apply to you, ask yourself what you think you know about that topic, how confident you are in that knowledge, and, most importantly, how you think you know it. Your mental litany should go, “what do I think I know and how do I think I know it?” Instead of feeling defensive about being wrong and making up excuses for maintaining an erroneous belief, (which is our default stance - this is part of another powerful metal effect called cognitive dissonance), train yourself to get pleasure when you update your beliefs when presented with compelling evidence that you were wrong. The reason I think it’s useful to discuss Dunning-Kruger in this series of posts is that I think architecture is probably more rife with it than other learned professions. That begins in our education, in which for most schools training architecture students how much they don’t know simply isn’t part of the curriculum. Instead, in architecture school, ideas (“concepts”) stand in for knowledge and learning how to draw is given heavier weight than learning the profession. Architecture students are taught a lot about design but next to nothing about building technology, specifications, or practice. [Aside -- Speaking of weight, back when I was in school we used Sweets™ Catalogs as ballast for models, but it was also enlightening to page through them just to see the myriad building products that exist in the world of which I had so little knowledge. Also, Sweets ™ was the first place I encountered MasterFormat divisions. Now, I don’t think the paper version of Sweets™ even exists.] Contrast architectural with medical school: there the knowledge gap between the students and practitioners is constantly being emphasized and made clear through verbal and written assessments. Medical students are reminded over and over that they have massive amounts to learn, and taught to be humble. Maybe it’s a status thing; architects tend to believe architecture is a high status profession. Most architects believe that having more completed projects in the world gives them higher status and more knowledge and the right to claim to be wise and espouse ‘deep thoughts’. However, we’d be more wise to understand and remember that Dunning-Kruger shows that what feels like knowledge often isn’t anything more than mind clutter. Skeptical blogger and podcaster Steve Novella wrote this when offering advice on how to combat Dunning-Kruger in yourself: Think about some area in which you have a great deal of knowledge in the expert to mastery level (or maybe just a special interest with above average knowledge). Now, think about how much the average person knows about your area of specialty. Not only do they know comparatively very little, they likely have no idea how little they know, and how much specialized knowledge even exists. Here comes the critical part – now realize that you are as ignorant as the average person is every other area of knowledge in which you are not expert. Assume you know less than you think you know. Assume that stuff you believe now is wrong (and be ready to change your mind).

1 Comment

Contributed by Liz O'Sullivan In January a little ways back, the Denver Chapter of the Construction Specifications Institute hosted a chapter meeting with a Panel Discussion on Substitutions including an owner’s rep, a general contractor, a subcontractor, an architecture firm’s construction contract administrator, and a specifier. Here’s some of what we learned.

Many Owners Welcome Substitutions. The biggest divergence of opinions was about owners’ positions on substitutions. The loud and clear message from the owner’s rep was that owners welcome substitutions, and that many are frustrated with architects’ and specifiers’ reluctance to entertain substitutions. In the eyes of the owner’s rep, there are two crucial things – cost and schedule. Since time is money in construction, schedule is very important to owners, so even a substitution that costs more money but saves time is likely to be favorably received by an owner. Owners wish that more architects and specifiers understood the overall impact of substitutions, time- and money- wise. (It’s important to note that the owner’s rep on the panel primarily represents developers, and recent projects have been multifamily residential projects.) The specifier pointed out that for private work, substitutions can be good because they give the design team an opportunity to evaluate things they may not have evaluated when they first prepared the documents. The subcontractor thinks that substitutions are an opportunity for the owner to get a better value. With the developments and changes in products and assemblies that happen all the time, architects and specifiers can’t keep up. Subcontractors, who are specialists in their areas, can keep up, and may be able to offer better solutions. But Some Owners Don’t Want Substitutions. The specifier reminded us that many owners, especially in the public sector, want what they know has worked, and do not want substitutions. Owners such as municipalities, public school districts, and universities may own and maintain many buildings, and need maintenance procedures to be the same from building to building. Public owners’ requirements are sometimes outdated, however, and the specifier does not always have the opportunity to explain to the owner that several of their listed acceptable manufacturers no longer exist. Substitutions Scare Architects. Substitutions scare architects, and for good reason. They spend a lot of time designing around a particular product – that’s why that particular product is specified. Architects worry about how many details in the drawings will be affected – and will no longer be correct – because of a particular substitution. During the months-long design process, design decisions are followed all the way through everything that’s affected by them. There’s often no time to go back and do this again during construction. And when design changes have to be made due to a substitution, it is hard to be sure one has gone back and checked every possible thing that could be affected, as was done when the design was first developed. This is not only due to time constraints, it’s also because this is not how the design process naturally flows. Architects also wonder if the owner is getting something of a lesser value on the project when a substitution has been accepted because the owner was attracted to cost savings. The architect knows that the owner is happy to be getting something cheaper, but the architect worries that the owner is giving up something of greater value or performance (the specified item), and the general contractor or subcontractor is the one actually saving more money on the substitution. People Have Different Ideas About What a Substitution Is. Panelists agreed that different team members on a design and construction project do not agree about exactly what a substitution is. The general contractor pointed out that team members treat substitutions differently depending on the project delivery method. Substitutions are treated differently on hard bid (design-bid-build), negotiated (construction-manager-at-risk or construction manager/general contractor), and design-build projects. The general contractor doesn’t want to receive substitutions submitted by subs on hard bid (design-bid-build) projects, because they are usually submitted to the general contractor without enough time to get them approved by the architect prior to the bid. The general contractor then has to decide whether or not to use the price associated with that substitution. If the general contractor is not the low bidder, it doesn’t matter, so there’s an incentive to use the price associated with an unapproved substitution. But if he uses that number and then the substitution is not accepted when submitted to the architect after the bid, he’s losing money. On negotiated projects, the general contractor wants to see substitutions, get pricing, explain to the owner and the architect that if this product is used instead of a specified product, the owner can save money, or the schedule can be shortened. There’s more of a collaborative effort on negotiated projects. The specifier (of course) read us the definition of a substitution from MasterSpec. It’s vague. Most of the industry probably agrees that “the devil is in the details” on this issue. We agree that a substitution is a change, but what kind of a change, and how a substitution is supposed to be evaluated, are where the differences of opinion and misunderstandings occur. The owner and design team need to define how casual or formal the process for evaluating substitution requests is. The specifier believes that part of his job is to define that evaluation process succinctly. Contributed by Eric D. Lussier I’m quickly approaching eleven years working in and around indoor flooring, focusing mainly on sport and synthetic surfaces. Eleven years of projects of all shapes and sizes ranging from 250 square foot residential basements to 30,000 square foot college field houses. Eleven years of existing conditions, renovations, rehabilitations and new construction and the one constant that rears its ugly head on almost each job are substrate conditions, and especially concrete moisture. Conversely, said moisture issues are seemingly new news to whomever I am working with: whether that is architects, construction managers, general contractors or end users.

There are more than a few instances that can lead to high moisture in a concrete slab. Whether it is an over-watered pour, a lack of a quality vapor barrier, a compromised vapor barrier, or a missing one entirely (either from degradation or lack of placement), a fast track installation with insufficient time for the concrete to dry, an inoperable or missing HVAC system or a handful of other events. No matter the occurrence, it can all equate to the same headaches after the fact. Normally fingers are pointed, voices are raised, materials are ripped out and unnecessary time and money is spent to potentially repair or replace flooring that perhaps should have never been installed to begin with. Industry-speak may call it “flooring failure” but most of the time the flooring is performing exactly as it is supposed to. The adhesive on the other hand, may be completely failing. New construction technologies have our buildings tighter than ever. With the use of a proper vapor barrier removing the ground from the equation, concrete moisture has no place to go but up and through the slab. When placing a fully adhered, non-breathing floor, such as a heat-welded sheet vinyl on the slab, concrete moisture in an untreated slab travels up and out, trying to push through the adhesive and new floor in the process. Even though the norm in the industry has raised from 3 lbs. of moisture to 5 lbs., as per ASTM F1869-11 (Standard Test Method for Measuring Moisture Vapor Emission Rate of Concrete Subfloor Using Anhydrous Calcium Chloride), that limit can take substantial time to achieve when it comes to new construction. Speaking of norms in the industry, thankfully most flooring manufacturers have moved away from recognizing calcium chloride testing (which is more of a snapshot of what is happening emanating from just the top of the slab) towards in-slab relative humidity (RH) testing (what is going on inside the slab). Testing as per ASTM F2170-11 (Standard Test Method for Determining Relative Humidity in Concrete Floor Slabs Using In-Situ Probes (has become easier over the last handful of years with developed equipment, including testing probes that can be left in the slab and reusable digital probes. It is always recommended that an independent third-party is specified to test the concrete for moisture and not the General Contractor or flooring contractor themselves. It could be viewed that each party has a vested interest in ensuring that results are swayed their way. If you are looking for a certified concrete moisture testing party, the International Concrete Repair Institute offers a moisture testing certification program and you can search the certified testers here. |

AboutLet's Fix Construction is an avenue to offer creative solutions, separate myths from facts and erase misconceptions about the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry. Check out Cherise's latest podcast

Get blog post notifications hereArchives

March 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed